Macroeconomic Impact of COVID-19

Macroeconomic Impact of COVID-19

COVID-19’s epidemiological dynamics are still rapidly evolving in India, rendering difficult an accurate assessment of its full macroeconomic effects. In this scenario, an approach employing a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model built on New Keynesian foundations provides a tentative and proximate assessment of the likely impact of COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdown on the Indian economy.

The model has three main economic agents, viz., households, firms and the government. COVID-19 and the lockdown can impact the economy through multiple channels (Eichenbaum et al., 2020; Faria-e-Castro, 2020; Yang et al., 2020). Because of lockdown, households have to stay at home and therefore, reduce labour supply to firms; consumption falls due to non-availability of non-essential items and fall in income; and restricted people-to-people contact stalls the momentum of the pandemic.

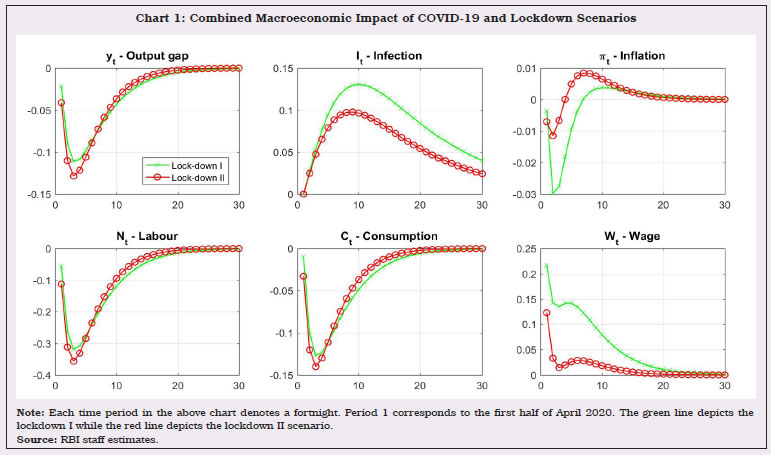

The model is calibrated2 so that infections peak around the second half of August 2020 [based on the predictions of a generalised Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered (SEIR) model for India] and the output gap widens to about (-) 12 per cent of potential output when the economy is worst hit. Two scenarios are envisaged: the first, i.e., lockdown I, impacts the supply side of the economy by decreasing the labour supply and its productivity. The second scenario, i.e., lockdown II, additionally considers the increase in marginal cost.

Inflation falls under both scenarios mainly because of a fall in demand; under lockdown II, however, the decline in inflation is less steep and short-lived. Firms respond to the squeeze in profits, due to higher marginal costs, by curtailing production and labour demand. Wages see a lower rise and economy goes through a large contraction. However, the recovery from the pandemic is faster in this scenario on account of fewer opportunities for people-to-people interactions. Under scenario I by contrast, production retrenchment is less severe, but demand contraction is more pronounced due to a rise in infections. Thus, the economy undergoes a deeper contraction under lockdown II, but recovery from the pandemic is faster (Chart 1).

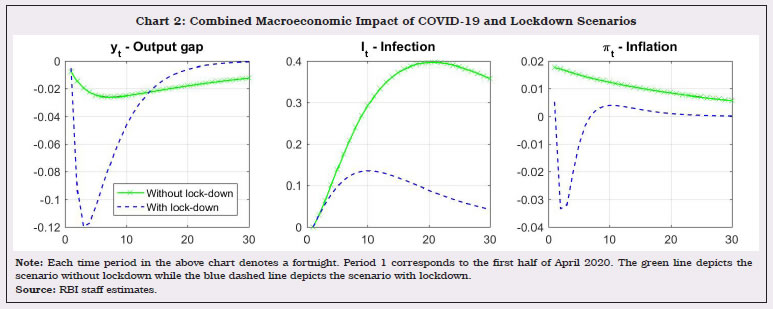

In order to evaluate the macroeconomic implications of scenarios I and II, it is worthwhile to simulate a third scenario in which the government does not impose a lockdown (Chart 2).

This results in a more widespread pandemic, which peaks in the second half of January 2021 with a very slow recovery. This causes a persistent labour shortage and the supply shock produces a lasting impact on inflation and the output gap, which corresponds to a permanent upward shift in inflation and a downward shift in potential output, respectively.

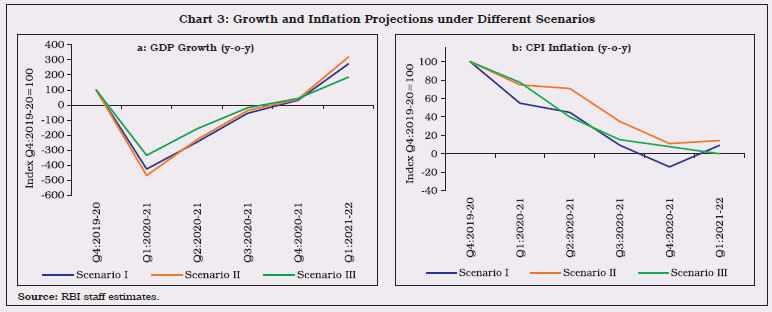

In scenario II, which envisages a second lockdown, the decline in economic activity is expected to reach its trough in Q1:2020-21 and growth turns positive from Q4:2020-213 (Chart 3a). Inflation, which was high at 6.7 per cent in Q4:2019-20, is projected to ease till Q4:2020-21 (Chart 3b).

In sum, COVID-19 without the associated lockdown acts like a supply shock which causes a persistent rise in inflation and a permanent loss of output. As per Scenario II, which looks closer to the reality, the decline in economic activity reaches its trough in Q1:2020-21 and recovers thereafter, albeit at a gradual pace, with growth turning positive from Q4:2020-21.

Comments

Post a Comment